"The attorneys pointed to 450 rentals, representing 17 percent of Croman’s real estate portfolio, that are sitting vacant, the bulk of which are “free market and commercial.”

"Croman has purchased more than a dozen properties since his release from prison."

Mar. 19, 2021 10:30 AM

By Kathryn Brenzel

Share on FacebookShare on TwitterShare on LinkedinShare via EmailShare via Shortlink

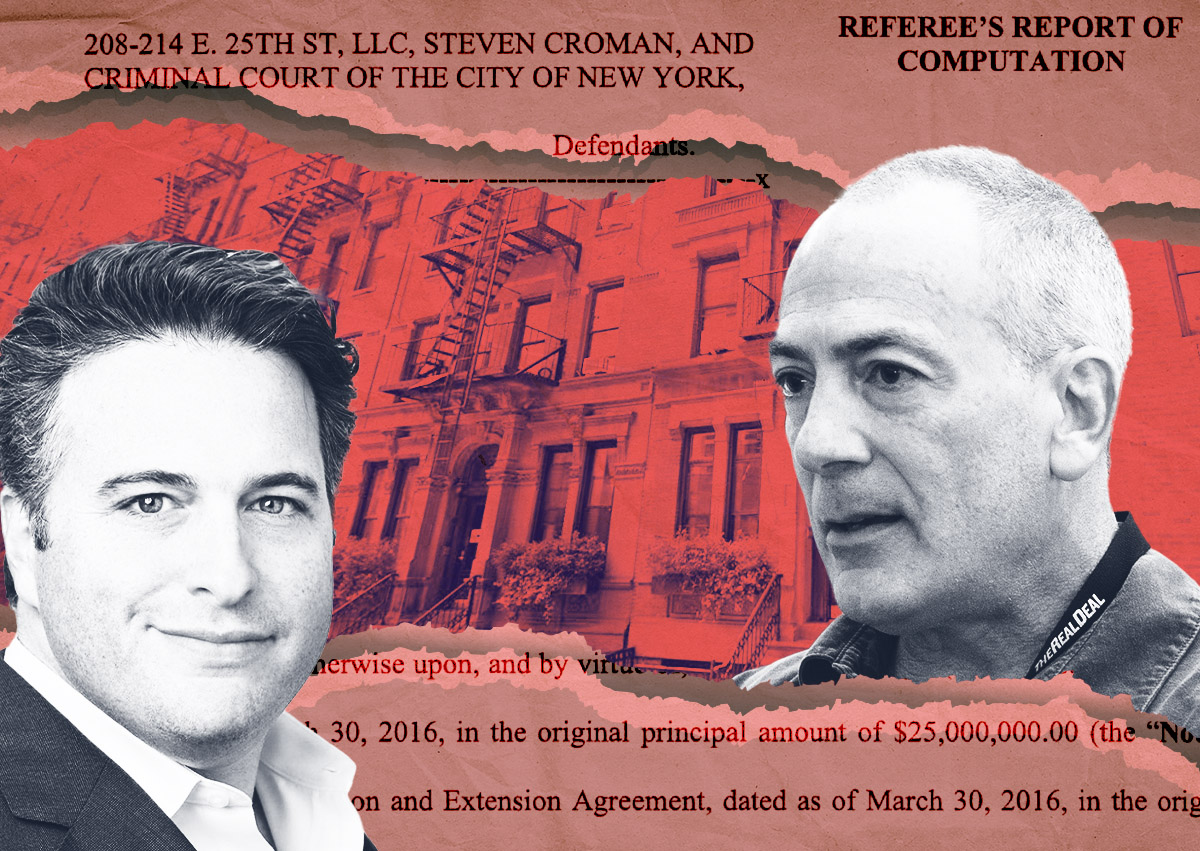

Landlord Steve Croman has bought himself extra time to pay off the remaining $2 million he owes tenants, thanks to hundreds of vacancies across his rental portfolio.

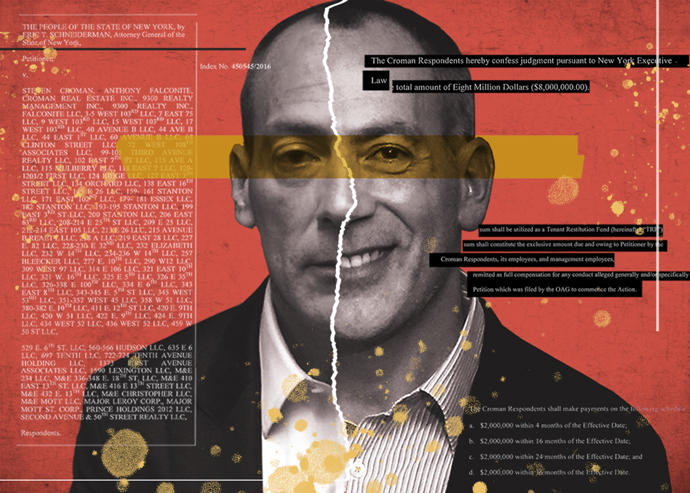

Croman agreed in 2017 to pay tenants $8 million to settle allegations that he harassed them out of their rent-regulated apartments. The deadline for paying the final $2 million installment of the settlement was Dec. 31, 2020.

In a Dec. 11 email, Croman’s attorneys said he couldn’t make the payment in a “timely manner,” due to the pandemic and its resulting economic downturn. The attorneys pointed to 450 rentals, representing 17 percent of Croman’s real estate portfolio, that are sitting vacant, the bulk of which are “free market and commercial.”

As a result, New York County Supreme Court Judge Shlomo Hagler set up a new schedule for Croman, allowing him to make 27 monthly payments of just over $74,000 between January 2021 and March 2023.

But some are unhappy about the extension. Cynthia Chaffee, a founder of the Stop Croman Coalition who lives in one of the landlord’s buildings on East 18th Street, said she didn’t understand why the judge granted Croman’s request. She questioned what proof he was required to provide to demonstrate that he was financially hurting, noting that Croman has purchased more than a dozen properties since his release from prison.

“How can he claim that he doesn’t have the money to pay the restitution?” she asked. “Are they just taking him on his word?”

Assembly member Linda Rosenthal said the vacancies and resulting financial hardship are likely Croman’s own doing. The landlord has previously been accused of using illegal tactics to drive out tenants, then flipping the units, using a now-defunct provision of the state’s rent law that allowed the deregulation of vacant apartments.

“I call this the orphan defense,” she said. “It’s like someone killed their parents, and are on trial and then say, ‘Have pity, I’m an orphan.’”

She added, “We know that he has held units off the market for years.”

Rosenthal said the state needs to investigate if Croman intentionally kept units vacant, a practice called warehousing that landlords warned would result from the 2019 changes to the rent law. New York doesn’t prohibit landlords from keeping apartments vacant, though Rosenthal has introduced legislation that would fine owners who keep rent-regulated apartments empty.

An attorney for Croman’s company, which recently rebranded as Centennial Properties NY, said that the reason for the change in the payment schedule was provided to the state Attorney General’s office and the court.

“The company remains focused on diligently implementing the settlement agreement in line with its focus on using best practices to provide quality housing for its residents,” the attorney said. He would not provide further details on the vacant rentals.

A representative from the Attorney General’s office declined to comment.

Earlier this month, Rosenthal wrote a letter calling on the state’s housing regulator to audit Croman’s portfolio to see if the units were vacant before the pandemic. A representative for the Division of Homes and Community Renewal said the agency was reviewing the letter but could not confirm or comment on any pending audits.

“New York State has zero tolerance for landlords who harass, intimidate or unlawfully overcharge tenants,” an agency spokesperson said in a statement, which noted that HCR’s Tenant Protection Unit had made the criminal case referral that led to Croman’s conviction.

Croman was convicted in 2017 on mortgage and tax fraud charges and served eight months of a one-year prison sentence. He subsequently settled harassment allegations in a civil case by agreeing to pay tenants $8 million, and temporarily turned over management of more than 100 buildings to New York City Management, a private company selected by the state.

He has since faced several other lawsuits. Most recently, tenants of 159 Stanton Street have alleged that more than half of the building has been empty for more than five years and that the property is plagued by a rodent and roach infestation, the Village Sun reported.

Under Croman’s consent decree with the court, the landlord could request to take back control of up to 20 buildings on the one- and three-year anniversary of the agreement. He is slated to resume management of all of his properties in 2023.

“Not one building should be back to him until every penny of the restitution is paid,” Chaffee said. “The tenants feel that he has gotten off with a slap on the wrist.”

"Croman has purchased more than a dozen properties since his release from prison."

Steve Croman Gets Deadline Extension For Tenant Payments

Landlord Steve Croman has until 2023 to pay off the final $2 million of $8 million in restitution owed to tenants.

therealdeal.com

Croman gets until 2023 to pay final $2M in tenant restitution

Landlord’s attorneys say Covid has led to vacant units

New YorkMar. 19, 2021 10:30 AM

By Kathryn Brenzel

Share on FacebookShare on TwitterShare on LinkedinShare via EmailShare via Shortlink

Landlord Steve Croman has bought himself extra time to pay off the remaining $2 million he owes tenants, thanks to hundreds of vacancies across his rental portfolio.

Croman agreed in 2017 to pay tenants $8 million to settle allegations that he harassed them out of their rent-regulated apartments. The deadline for paying the final $2 million installment of the settlement was Dec. 31, 2020.

In a Dec. 11 email, Croman’s attorneys said he couldn’t make the payment in a “timely manner,” due to the pandemic and its resulting economic downturn. The attorneys pointed to 450 rentals, representing 17 percent of Croman’s real estate portfolio, that are sitting vacant, the bulk of which are “free market and commercial.”

As a result, New York County Supreme Court Judge Shlomo Hagler set up a new schedule for Croman, allowing him to make 27 monthly payments of just over $74,000 between January 2021 and March 2023.

But some are unhappy about the extension. Cynthia Chaffee, a founder of the Stop Croman Coalition who lives in one of the landlord’s buildings on East 18th Street, said she didn’t understand why the judge granted Croman’s request. She questioned what proof he was required to provide to demonstrate that he was financially hurting, noting that Croman has purchased more than a dozen properties since his release from prison.

“How can he claim that he doesn’t have the money to pay the restitution?” she asked. “Are they just taking him on his word?”

Assembly member Linda Rosenthal said the vacancies and resulting financial hardship are likely Croman’s own doing. The landlord has previously been accused of using illegal tactics to drive out tenants, then flipping the units, using a now-defunct provision of the state’s rent law that allowed the deregulation of vacant apartments.

“I call this the orphan defense,” she said. “It’s like someone killed their parents, and are on trial and then say, ‘Have pity, I’m an orphan.’”

She added, “We know that he has held units off the market for years.”

Rosenthal said the state needs to investigate if Croman intentionally kept units vacant, a practice called warehousing that landlords warned would result from the 2019 changes to the rent law. New York doesn’t prohibit landlords from keeping apartments vacant, though Rosenthal has introduced legislation that would fine owners who keep rent-regulated apartments empty.

An attorney for Croman’s company, which recently rebranded as Centennial Properties NY, said that the reason for the change in the payment schedule was provided to the state Attorney General’s office and the court.

“The company remains focused on diligently implementing the settlement agreement in line with its focus on using best practices to provide quality housing for its residents,” the attorney said. He would not provide further details on the vacant rentals.

A representative from the Attorney General’s office declined to comment.

Earlier this month, Rosenthal wrote a letter calling on the state’s housing regulator to audit Croman’s portfolio to see if the units were vacant before the pandemic. A representative for the Division of Homes and Community Renewal said the agency was reviewing the letter but could not confirm or comment on any pending audits.

“New York State has zero tolerance for landlords who harass, intimidate or unlawfully overcharge tenants,” an agency spokesperson said in a statement, which noted that HCR’s Tenant Protection Unit had made the criminal case referral that led to Croman’s conviction.

Croman was convicted in 2017 on mortgage and tax fraud charges and served eight months of a one-year prison sentence. He subsequently settled harassment allegations in a civil case by agreeing to pay tenants $8 million, and temporarily turned over management of more than 100 buildings to New York City Management, a private company selected by the state.

He has since faced several other lawsuits. Most recently, tenants of 159 Stanton Street have alleged that more than half of the building has been empty for more than five years and that the property is plagued by a rodent and roach infestation, the Village Sun reported.

Under Croman’s consent decree with the court, the landlord could request to take back control of up to 20 buildings on the one- and three-year anniversary of the agreement. He is slated to resume management of all of his properties in 2023.

“Not one building should be back to him until every penny of the restitution is paid,” Chaffee said. “The tenants feel that he has gotten off with a slap on the wrist.”