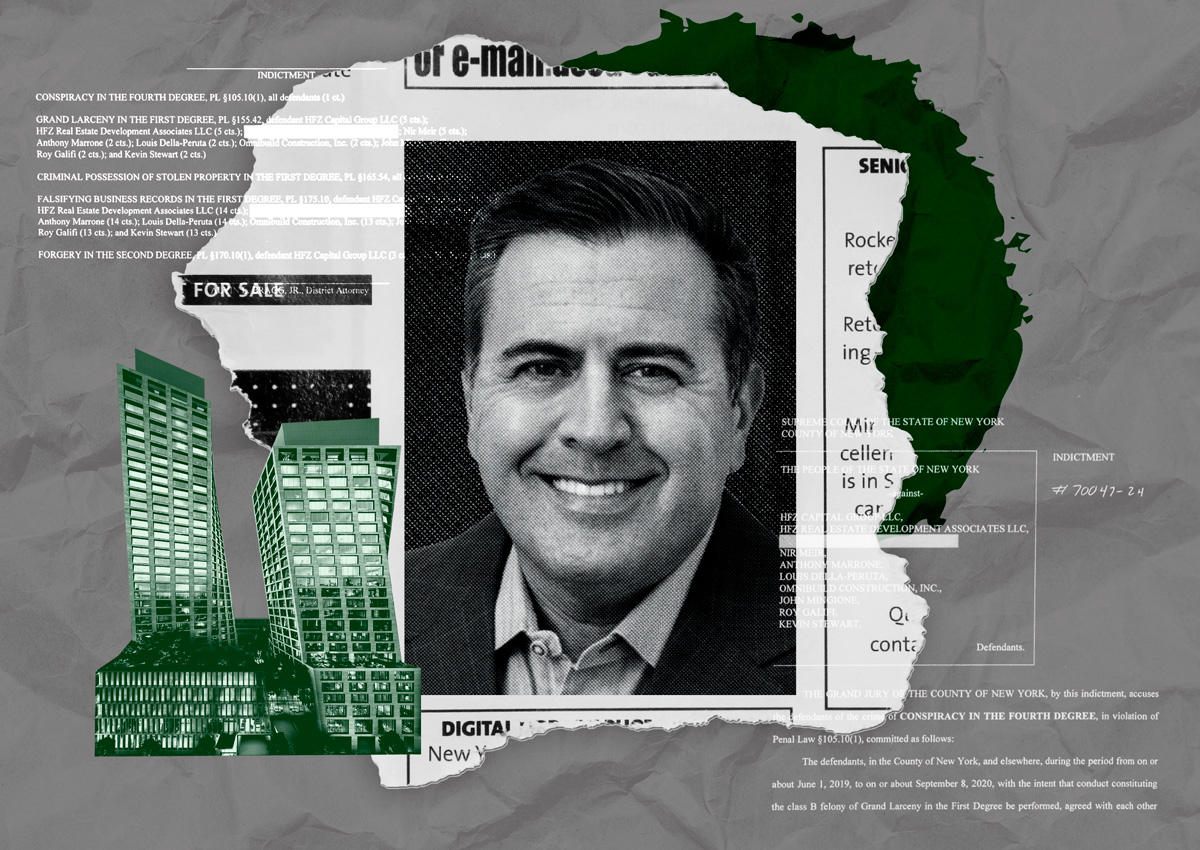

Large construction companies often emerge from corruption cases unscathed, even when directly involved in wrongdoing.

therealdeal.com

Cracks in the foundation: Construction’s kickback problem

Construction is inherently vulnerable to corruption, but contractors have a way of surviving it

A small Queens glass company sent out a letter in 2017, alerting clients that it had fired three of its employees. It did not say why, but that became clear soon enough.

Authorities had discovered an alleged bribery scheme centered not on little-known Jonathan Metal & Glass but on Turner Construction and Bloomberg. Executives from the two giant firms were charged with accepting millions of dollars’ worth of payoffs in exchange for inflating interior construction contracts.

Federal authorities raided Turner’s offices in October 2017, roughly a week before the glass shop revealed the firings. One of the terminated employees was later accused in the scheme, along with nearly two dozen other subcontractors and vendors.

The federal and state criminal cases against former Turner and Bloomberg employees, as well as the subcontractors, are only now nearing a conclusion. Four former executives of the big firms have pleaded guilty to tax evasion, theft and other charges.

By marking up construction costs at Bloomberg offices, executives stole at least $15 million from the media and financial information company, authorities said. They now face prison.

As for Turner, although its client was ripped off, the firm was not charged, suffered no apparent blow to its reputation and has continued to win large contracts. Which surprised absolutely no one.

Large construction companies often emerge from corruption cases relatively unscathed, even when found to be directly involved in wrongdoing. They pay a fine, issue an apologetic statement and continue to bid on work.

But the Turner case also underscores how vulnerable construction is to malfeasance and the persistent appetite of industry players to cheat at every level of the process.

“You can never be content with the controls that you set up because people who are looking to pad their invoices are vigilant as well, in a negative sense,” said Dennis Walsh, a former prosecutor with the New York attorney general’s Organized Crime Task Force and a consultant with Guidepost Solutions. “Companies need to think in a forward way and be mindful of the tireless efforts of some contractors to exploit opportunities.”

The scheme

In September 2017, a project superintendent for Turner, Vito Nigro, sent a cryptic text message to an air conditioning subcontractor.

“When u bringing lunch so we’re done. The other guy is getting married,” he wrote, according to state prosecutors.

He was referring not to food but to a series of illicit cash payments that were used in part, to help pay for then-Bloomberg construction manager Michael Campana’s wedding photographer, prosecutors allege. Nigro repeatedly referred to bribes in lunch terms, most often as “sandwiches,” according to the 2018 indictment.

The two, along with more than a dozen others, were charged with conspiring with various subcontractors and vendors to award work to certain companies, artificially driving up the costs of construction work at Bloomberg’s offices at 120 Park Avenue and 919 Third Avenue.

In return, the subcontractors allegedly provided cash bribes and other kickbacks, including vacations and home renovations, to executives at Bloomberg and Turner. This went on for six and a half years.

Finally, a month after Nigro’s message about “lunch,” New York State Police officers and investigators

crashed the party.

Prosecutors said at the time that the graft turned the New Jersey home of Anthony Guzzone, Bloomberg’s head of global construction, into a “

palace.”

A separate federal indictment slapped tax-evasion charges on the executives, who had not reported the illicit benefits to the IRS. Attorneys for Nigro and Campana did not comment for this story.

The scheme was not novel in the annals of construction fraud. In the past three decades, New York’s largest construction managers have paid millions in fines and penalties to settle similar allegations. But the case was notable for a few key reasons.

For one, Bloomberg and Turner are huge, sophisticated companies. Bloomberg, founded by former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg and headquartered on Lexington Avenue, is worth as much as $60 billion, according to Burton-Taylor International Consulting. Turner bills itself as the country’s largest construction manager. Its global revenue last year was $14.66 billion,

according to ENR.

Turner is a subsidiary of German engineering giant Hochtief, which acquired the New York–based construction manager in 1999 for $263 million. Since then, Turner has expanded across the U.S. — where it now has more than 40 offices — and internationally.

But size can make corruption harder to find. “Rogue actors” can keep misdeeds under the radar for an extended period at a large company, especially when projects are worth tens of millions of dollars, according to Jodie Kane, head of the Manhattan district attorney’s Rackets Bureau.

“It’s easy to skim off what would still be a considerable amount of money for many of us but, in the larger view of the project, is a small fraction,” she said. The alleged involvement of top Bloomberg executives likely made the scheme even harder to stop.

“I think it’s easy to go undetected for a long time, even with very rigorous internal compliance and especially when it’s the gatekeeper, who’s supposed to be identifying the compliance, who ends up being a bad actor,” Kane said. “Really, that’s the worst of all possible worlds.”

Some elements of a construction contract can be readily inflated if they have no fixed value, such as responding to conditions on a site that emerge during the building process.

“If there was a stock that you could buy for a dollar, and someone paid $1.10, you’d know something was up,” said Ronald Goldstock, a private, independent inspector general and construction integrity monitor who was once director of the New York State Organized Crime Task Force. “The construction industry by its very nature is rife with the possibilities of bribery and extortion.”

Diana Florence, who spent 25 years at the Manhattan district attorney’s office and headed its Construction Fraud Task Force, said looking at a company’s culture is key in determining its culpability.

“There also has to be fairness,” she said. “You can’t indict an entire company, and you shouldn’t, based on a rogue employee.”

But some believe Bloomberg should have been prepared for this kind of scheme. Bloomberg’s previous construction manager, Structure Tone, was also accused of overbilling the firm, as well as other clients. Structure Tone pleaded guilty in 2014 to falsifying business records.

Also, Nastasi & Associates, a carpentry subcontractor, had warned Bloomberg and Turner of problems with their bidding processes, according to lawsuits filed after the criminal federal and state cases were revealed.

The company’s owner, Anthony Nastasi, claims in the suits that after he raised questions, his company was abruptly fired from a Bloomberg project and then blocked from bidding on others, which destroyed his company.

“This is how Turner runs its business,” the lawsuit states. “Everyone knows the risk of crossing Turner, and Turner does not hesitate to impose its enormous market power on subcontractors that depend on Turner for work.”

The suit, which a Turner spokesperson said has “no merit” and was dismissed in March in a decision now being appealed, also contends that both companies ignored “red flags” that the schemes “reached the highest levels of these companies, permeating through many departments and levels of employees in different areas of the construction business.”

“Not only should their compliance programs have caught this scheme, based on the breadth and brazenness of the conduct by their highest-level executives,” the lawsuit claims, “but these companies have long been on alert that their employees, including their highest-level executives, were susceptible to it.”

Moving on

Three years after being revealed, the federal and state cases against the Turner and Bloomberg executives are coming to a close.

Guzzone, whom prosecutors referred to as the scheme’s mastermind, faces up to five years in prison on the federal tax evasion charge and three to nine years for grand larceny in the state case. Ronald Olson, former Turner vice president and deputy operation manager, faces the same sentences. Campana was sentenced to 24 months in prison in the federal case and faces one year in the state case, after pleading guilty to tax evasion and money laundering, respectively.

An attorney for Guzzone, Alex Spiro, said in a statement that his client has “accepted responsibility for accepting gratuities and not disclosing certain matters on his taxes and will further explain the circumstances in court.” A lawyer for Olson did not comment.

One employee of Jonathan Metal & Glass, Frank Zustovich, pleaded guilty to stealing $50,000 from Bloomberg and agreed to provide authorities with the names of Bloomberg and Turner executives, according to the

New York Times.

Zustovich, along with at least one other employee fired from Jonathan Metal, now work for another company, GFC Ornamental Metal & Glass, according to LinkedIn.

Turner, meanwhile, seems to have emerged with nary a scratch. In New York, the company is serving as construction manager for the Spiral, Tishman Speyer’s Bjarke Ingels–designed office tower. In May it was

selected to build out the interiors of Ernst & Young’s offices spanning 18 floors at One Manhattan West. Vornado Realty Trust recently tapped the company to oversee the redevelopment of 2 Penn Plaza.

“Clients recognize that the actions of two former employees do not reflect Turner’s true character of honesty and integrity,” the Turner spokesperson said about the Bloomberg case. “Turner actively cooperated with law enforcement throughout the investigation and applauds their efforts in prosecuting these individuals.”

Kane said larger companies are typically better equipped to weather bad press and reputational damage that accompanies criminal convictions. Smaller companies will sometimes shut down and reopen under a new name, she said.

But the government rarely tries to put firms out of business, a lesson learned when the conviction of Arthur Andersen in the 2001 Enron scandal triggered the disintegration of the accounting giant, costing thousands of employees their jobs.

In determining whether to go after the company itself, prosecutors consider how many people it employs and if there is a way to remedy criminal activity while keeping it in business, according to Kane.

“Many of these companies, despite criminal wrongdoing, they do good work in the construction industry,” she said. “So if you can find a way to clean up the culture of the company, but to keep the workers employed, that’s one of the things that we try to do.”

Louis Coletti, president of the Building Trades Employers Association, called the cases against Turner — a member of his group — and Bloomberg employees an “aberration.”

“At the end of the day, human beings will try to take advantage of any system,” he said. “We do all we can to prevent it, but if anybody goes asunder, rest assured they will be terminated and have been terminated.”

Indeed, executives were caught. But by the government, not by the companies. And given the weaknesses inherent in construction contracting, it appears certain such crimes will happen again.

In addition to increased corporate vigilance, Florence said, the government needs to make clear it is continuously watching for fraud. Otherwise, companies and their employees will continue to think the risk of getting caught is outweighed by potential rewards.

“It’s like Groundhog Day over and over,” she said.