Things got so bad at NYCHA that a Federal monitor was appointed for oversight. There have been moves to bring in various private entities through programs like RAD (Rental Assistance Demonstration). Now The Related Companies is taking its shot.

The New York-based company, in a joint venture with Essence Development, will carry out $366 million worth of repairs at over 2,000 NYCHA units in Chelsea. The entry into the public housing arena is a departure for Related, which is known for posh projects, although it has developed private affordable housing.

Under the Permanent Affordability Commitment Together initiative, or PACT, the developer will finance the improvements with future rental income from the apartments. The city makes that possible by shifting tenants’ primary rent subsidy to Section 8, a reliable federal funding stream against which developers can borrow.

The strategy has its own acronym, RAD, for Rental Assistance Demonstration. The de Blasio administration was so pleased with the initial RAD projects that it resolved to use it as much as possible to chip away at NYCHA’s $40 billion repair backlog.

Yet one band of critics remains convinced that bringing private interests such as Related into NYCHA will end badly for tenants.

“The #HudsonYards developer will annex public housing in Chelsea in order to clear it out,” Fight For NYCHA tweeted Wednesday morning upon learning that Related would take over repairs at Fulton, Chelsea, Chelsea Addition and Elliott Houses.

The group’s use of verbs like “annex” infuriates NYCHA, which has spent several years assuring tenants it retains ownership of the properties and that they will remain public housing, where rent cannot exceed 30 percent of a tenant’s income.

Opponents also rankle tenant leaders who see the program as an answer to the maintenance nightmare that NYCHA has failed for decades to solve on its own.

Miguel Acevedo, president of the Fulton Houses Tenant Association, a part of the working group organized to discuss the future of the Chelsea NYCHA developments, denounced Fight For NYCHA’s claims, saying the group was not present at meetings with Essence and Related and did not hear “what they had to say.”

“Instead they tweet outlandish and false accusations to stir up baseless fear,” Acevedo said in a statement. “We — NYCHA residents — are thrilled about this upcoming partnership with Essence and Related.”

Louis Flores, the tenant activist behind the opposition group, said NYCHA residents may have been misled by developers and lawmakers to believe the partnership would be beneficial. He claims Related could push out residents, demolish the buildings — five of which are high-rises — and redevelop the space.

“First of all, it’s very suspicious that the Related Companies would even bother with public housing since they are a luxury developer,” he said. “Secondly, given all the gentrification that has taken place in Chelsea and Hudson Yards, it’s not a surprise that they would want to get rid of public housing.”

But there is no plan to get rid of public housing. NYCHA officials have repeatedly assured that such a scenario cannot happen under the partnership program.

An early plan for the Chelsea PACT conversion called for demolishing two Fulton Houses buildings and replacing them with one larger tower, Politico reported. A working group later scrapped the recommendation.

However, Flores hypothesized that Related’s engineers could find it economically unfeasible to rehabilitate the building and recommend a demolition anyway.

“Just because they say they’re going to do something doesn’t make it true,” Flores said. “Just because they claim tenants are protected doesn’t make it true. That’s not what happened at Ocean Bay.”

Ocean Bay, in Queens, was the first NYCHA development to go through the rehabilitation program and is often cited by the agency as an example of how well it works. The Housing Authority even made a glowing video about it.

After private developers took over Ocean Bay Houses in Far Rockaway, the program’s flagship development, 80 households were evicted over the next 26 months — more than double the next highest development, City Limits reported in 2019.

But NYCHA said City Limits greatly overstated the number. And an executive for the management group, Wavecrest, told the publication that it “dutifully follows the official grievance procedures as outlined by the RAD program through NYCHA” and “works with residents to acquire assistance from various organizations based on their individual circumstance to reach an agreement whenever possible.”

Another fear that NYCHA has tried to tamp down is that private managers will be more aggressive about evicting tenants. City Limits reported in August 2019 that after taking over management of Ocean Bay in late 2016, the private partnership brought 290 cases in housing court against tenants for nonpayment of rent, or about one for every five units, and completed 80 evictions from January 2017 to February 2019.

But NYCHA told the New York Times that there were just 48 evictions in four years after RAD, the same number as in the four years prior.

Similar fears circulated after L+M Development Partners committed in February 2020 to $1.5 billion in improvements at 2,615 NYCHA units in Brooklyn and Manhattan in two separate ventures, one with Douglaston Development, SMJ Development and Dantes Partners and the other in Harlem with nonprofits Settlement Housing Fund and West Harlem Group Assistance.

Tenant groups attributed 151 evictions to L+M’s Ron Moelis in 2019, but that was less than 1 percent of his more than 18,000 households. According to L+M, the actual number was even lower, 72, or about 0.5 percent, and the firm evicted just five NYCHA tenants in 2019 out of roughly 1,600 NYCHA apartments under its management.

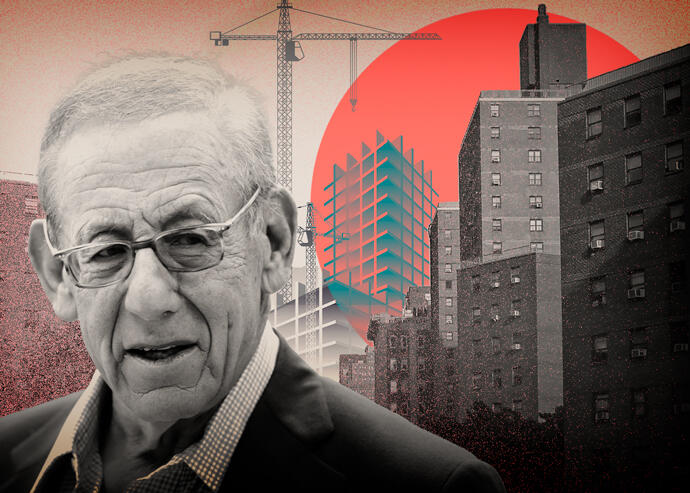

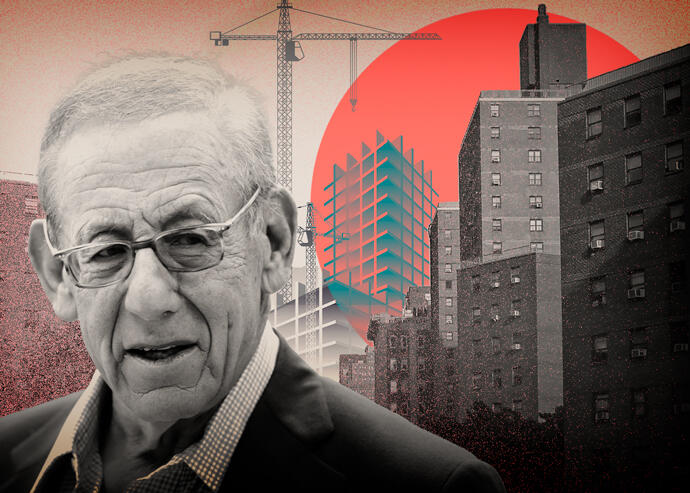

L+M is among the city’s largest providers of affordable housing, but Related is known for developing high-end Hudson Yards and for its billionaire chairman and Donald Trump fundraiser Stephen Ross, making it an easier target for critics of RAD.

Flores, of Fight For NYCHA, fears Related could set off a wave of displacement to buoy its bottom line. Nonpayment rates are higher in public housing developments where repairs have been neglected, as is the case in the Chelsea developments. And the state’s eviction moratorium is due to end Jan. 15.

Related declined to comment on Flores’ speculations. A NYCHA executive called Fight For NYCHA’s prophesizing about evictions and demolitions “completely unfounded.”

“NYCHA remains the owner of the property and residents’ rights and protections are built into the lease, and further protected by [federal] regulations,” said Jonathan Gouveia, NYCHA’s executive vice president of real estate development.

He underscored that the developers were picked at the residents’ behest.

Related Commits To $366M in NYCHA Repairs

The Related Companies will execute $366 million in repairs at a cluster of NYCHA developments in Chelsea. Tenant advocates fear it will evict tenants too.

therealdeal.com

Related wades into NYCHA — and becomes a target

Hudson Yards developer will oversee $366M in repairs to public housing

Related Companies is the latest private landlord to sign up for fixing New York City Housing Authority buildings — and for the disdain of activists who object to what they call privatization.The New York-based company, in a joint venture with Essence Development, will carry out $366 million worth of repairs at over 2,000 NYCHA units in Chelsea. The entry into the public housing arena is a departure for Related, which is known for posh projects, although it has developed private affordable housing.

Under the Permanent Affordability Commitment Together initiative, or PACT, the developer will finance the improvements with future rental income from the apartments. The city makes that possible by shifting tenants’ primary rent subsidy to Section 8, a reliable federal funding stream against which developers can borrow.

The strategy has its own acronym, RAD, for Rental Assistance Demonstration. The de Blasio administration was so pleased with the initial RAD projects that it resolved to use it as much as possible to chip away at NYCHA’s $40 billion repair backlog.

Yet one band of critics remains convinced that bringing private interests such as Related into NYCHA will end badly for tenants.

“The #HudsonYards developer will annex public housing in Chelsea in order to clear it out,” Fight For NYCHA tweeted Wednesday morning upon learning that Related would take over repairs at Fulton, Chelsea, Chelsea Addition and Elliott Houses.

The group’s use of verbs like “annex” infuriates NYCHA, which has spent several years assuring tenants it retains ownership of the properties and that they will remain public housing, where rent cannot exceed 30 percent of a tenant’s income.

Opponents also rankle tenant leaders who see the program as an answer to the maintenance nightmare that NYCHA has failed for decades to solve on its own.

Miguel Acevedo, president of the Fulton Houses Tenant Association, a part of the working group organized to discuss the future of the Chelsea NYCHA developments, denounced Fight For NYCHA’s claims, saying the group was not present at meetings with Essence and Related and did not hear “what they had to say.”

“Instead they tweet outlandish and false accusations to stir up baseless fear,” Acevedo said in a statement. “We — NYCHA residents — are thrilled about this upcoming partnership with Essence and Related.”

Louis Flores, the tenant activist behind the opposition group, said NYCHA residents may have been misled by developers and lawmakers to believe the partnership would be beneficial. He claims Related could push out residents, demolish the buildings — five of which are high-rises — and redevelop the space.

“First of all, it’s very suspicious that the Related Companies would even bother with public housing since they are a luxury developer,” he said. “Secondly, given all the gentrification that has taken place in Chelsea and Hudson Yards, it’s not a surprise that they would want to get rid of public housing.”

But there is no plan to get rid of public housing. NYCHA officials have repeatedly assured that such a scenario cannot happen under the partnership program.

An early plan for the Chelsea PACT conversion called for demolishing two Fulton Houses buildings and replacing them with one larger tower, Politico reported. A working group later scrapped the recommendation.

However, Flores hypothesized that Related’s engineers could find it economically unfeasible to rehabilitate the building and recommend a demolition anyway.

“Just because they say they’re going to do something doesn’t make it true,” Flores said. “Just because they claim tenants are protected doesn’t make it true. That’s not what happened at Ocean Bay.”

Ocean Bay, in Queens, was the first NYCHA development to go through the rehabilitation program and is often cited by the agency as an example of how well it works. The Housing Authority even made a glowing video about it.

After private developers took over Ocean Bay Houses in Far Rockaway, the program’s flagship development, 80 households were evicted over the next 26 months — more than double the next highest development, City Limits reported in 2019.

But NYCHA said City Limits greatly overstated the number. And an executive for the management group, Wavecrest, told the publication that it “dutifully follows the official grievance procedures as outlined by the RAD program through NYCHA” and “works with residents to acquire assistance from various organizations based on their individual circumstance to reach an agreement whenever possible.”

Another fear that NYCHA has tried to tamp down is that private managers will be more aggressive about evicting tenants. City Limits reported in August 2019 that after taking over management of Ocean Bay in late 2016, the private partnership brought 290 cases in housing court against tenants for nonpayment of rent, or about one for every five units, and completed 80 evictions from January 2017 to February 2019.

But NYCHA told the New York Times that there were just 48 evictions in four years after RAD, the same number as in the four years prior.

Similar fears circulated after L+M Development Partners committed in February 2020 to $1.5 billion in improvements at 2,615 NYCHA units in Brooklyn and Manhattan in two separate ventures, one with Douglaston Development, SMJ Development and Dantes Partners and the other in Harlem with nonprofits Settlement Housing Fund and West Harlem Group Assistance.

Tenant groups attributed 151 evictions to L+M’s Ron Moelis in 2019, but that was less than 1 percent of his more than 18,000 households. According to L+M, the actual number was even lower, 72, or about 0.5 percent, and the firm evicted just five NYCHA tenants in 2019 out of roughly 1,600 NYCHA apartments under its management.

L+M is among the city’s largest providers of affordable housing, but Related is known for developing high-end Hudson Yards and for its billionaire chairman and Donald Trump fundraiser Stephen Ross, making it an easier target for critics of RAD.

Flores, of Fight For NYCHA, fears Related could set off a wave of displacement to buoy its bottom line. Nonpayment rates are higher in public housing developments where repairs have been neglected, as is the case in the Chelsea developments. And the state’s eviction moratorium is due to end Jan. 15.

Related declined to comment on Flores’ speculations. A NYCHA executive called Fight For NYCHA’s prophesizing about evictions and demolitions “completely unfounded.”

“NYCHA remains the owner of the property and residents’ rights and protections are built into the lease, and further protected by [federal] regulations,” said Jonathan Gouveia, NYCHA’s executive vice president of real estate development.

He underscored that the developers were picked at the residents’ behest.